(Archived from Peter Ardren’s vintagebmwbikeservice.co.uk site)

O.K. So you’ve just bought a bike – or got one whose history you don’t know in detail. Maybe you’ve got one that you’ve had many happy years enjoyment on. You keep hearing advice to ‘Get the slingers checked’ but you’re not really sure what they are, what they do and why they should be checked when everything is working perfectly. ‘If it ain’t broke don’t fix it’, -right?

Wrong. In this case, very wrong. And I speak from painful experience. A well-respected BMW dealer gave me that advice many years ago after I bought my first slash 2. He should have known better. I had about a thousand very happy miles riding and falling in love with my R51 before the big ends went suddenly in a noisy and very expensive way. It’s a mistake I’ll never make again!

Slash 2s and most pre-war models didn’t have an oil filter as we know them today. But they wouldn’t have lasted long if they just recirculated their ever-increasingly-dirty oil. Instead of filters, they cleansed their oil by the use of slingers.

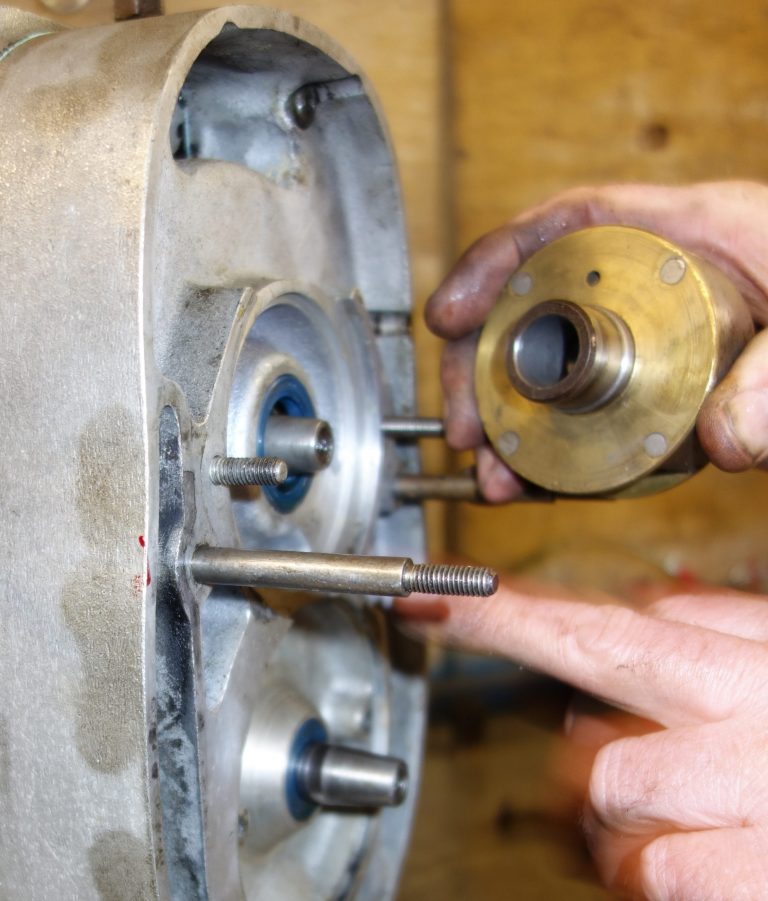

The slinger shown above is one of two, screwed at both ends of the crankshaft, they collect the oil that has been pumped through the main bearings. Just like a spin-dryer, the slingers work through centrifugal force. As they spin at engine revolution speed, any bits of crud in the oil are forced deep into the bottom of the metal lip. There they are compressed by centrifugal force together with other bits of crud to create an incredibly dense, compact layer, which gradually builds up and begins to fill the lip.

Filling the slinger lip takes time, of course – how long, I’ll discuss later. In the meantime what happens to all that oil that’s now been cleaned? Where does that go?

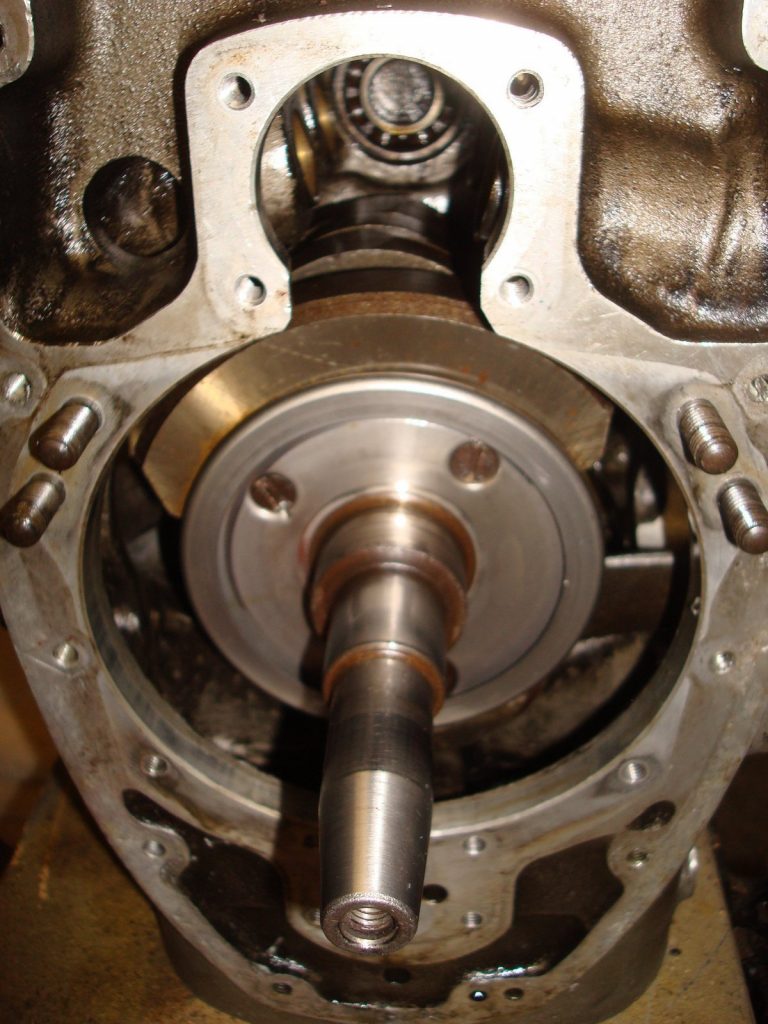

THAT, friends, is both the clever bit – and the problem. The slinger is always at either end of the crankshaft – fastened on with screws or, with some early models, machined into the crankshaft itself. But have a look at the crankshaft without its slinger fitted:

See the hole in the crankpin that the big end bearings run on? It’s at about 7.00 o’clock in the picture. This is normally difficult to see with the slinger on because the slinger fastens flat against it. The other side has an identical set up for the other crankpin and big end. That hole is where the clean oil goes – down the hole to feed the big ends. The slinger collects the oil in its lip and the cleaned oil is forced through the holes and into the bearings.

It works! It works well! BMW used this oil cleansing technique from the 30’s right through until the introduction of the slash 5 in 1969/70. So they knew they were doing something right.

But, inevitably, as the slingers do their job and collect more and more crud, the lips are going to fill. As they become shallower then they become less efficient at removing the oil. Worse, all the time the crud level is starting to approach the height of the big end oil feed hole. When it does so the slingers cease working. Dirty oil can flow directly into the big ends, causing rapid wear. Eventually, even this stops, for the big end holes become partially, then fully, blocked with bits of dirt. Adequate lubrication to the big ends ceases and the bearings have no alternative but to fail.

The picture below ( from a slash 6) shows the sort of thing that can happen in extreme circumstances through lubrication failure. Imagine those bits flying about inside the engine at 6000 revs!!

To be fair, though, partial, rather than full, oil starvation is more likely and the result won’t be quite as catastrophic. But you won’t gear far on the bike when the crankpin is in a state of near-terminal self-destruct.

So…. slingers need cleaning. Regularly. How do you know whether yours need doing now? You don’t! Not if you don’t know the full service history of the bike. or if the seller of the bike was bull-shitting when he said they’d just been cleaned. The bike will run sweet and you won’t know a thing. Then, if you’re lucky, you’ll get big end knock to warn you things are terminal. If you’re unlucky, as in the picture above, things can let go with a big bang!

How often do they need checking? BMW specified that early models such as the R11 and R12 should be stripped and checked EVERY YEAR!!! Slash 2s had much bigger slingers and so, thankfully, can be left a lot longer. The trouble is that BMW never gave any guidance on this and different experts will tell you different things. It all goes back again to the bike’s service history. Recently I worked on a bike that had just 30,000 genuine miles on it. It had completely full slingers and partially blocked big end oil feed holes. It needed a crank refurb. From the muck that lay everywhere in the engine and the consistency of the oil that crawled langorously out of the sump drain, I suspect its oil had rarely been changed.

I’ve also checked a bike at 45,000 miles that had almost empty slingers. But the owner (me) never goes beyond 1500 miles before changing the oil. If your bike has had regular servicing at BMW recommended intervals then I reckon you should consider getting it checked at 45,000 miles and certainly not go beyond 55,000. If you’re buying a bike and are at all unsure of the service history then factor the cost of an engine rebuild into your negotiations. It really isn’t worth taking a gamble!